AFSAN’S LONG DAY [2014]

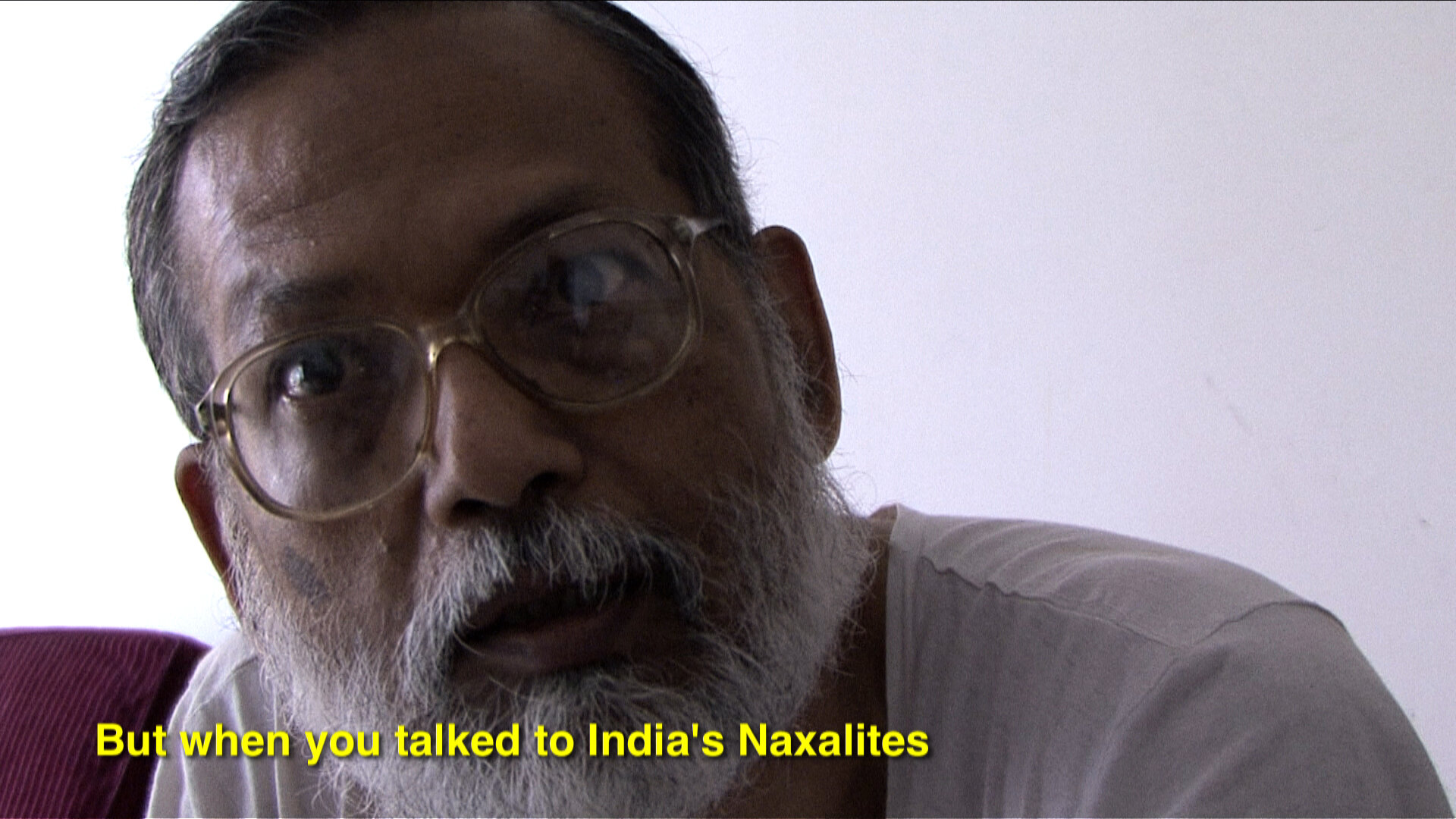

January 1974. Or, Autumn 1977. Now, in a Dhaka flat, historian Afsan Chowdhury writes diary entries in the form of magazine editorials. A voracious reader, he soon wearied of radicals who considered debate a waste of time; they thought the dialectic struggle could be short-circuited through the barrel of a gun. As with other times in this country’s short life, they misjudged the flow of water and history. Chowdhury uses the third person as a distancing device, and through stories of being a long-term diabetic, his time in exile (or immigration) in Toronto, and his navigation of the debris of a nation trapped by the past, he returns to the long day when he almost died. The men in uniform wanted to execute him after they found the Marxist pantheon in his library. “They thought I wrote them after I said so; I probably fit into the visual imagination of a radical. Beards are never trusted on young men. I argued with them about searching our house.” What else do you need to identify an enemy?

The narrator traverses Chowdhury’s disappointments, Sartre’s confrontation with a new Left that denied the nuances in his foreword to Fanon, and Fischer’s moment of reversal from Left pacifist clarity. The state’s overwhelming reaction made the counter-reaction inevitable; Heinrich Böll called it a “war of six against sixty million.”

The second film in the Young Man Was series premiered at Museum of Modern Art, New York (Doc Fortnight), and is inspired by Afsan Chowdhury’s diary—which also provides the series’ eponymous phrase, “the young man was … no longer a terrorist.” The accumulation of multiple memorials to the period was described by Kaelen Wilson-Goldie as a “revolutionary past meaningful in the sudden eruption of a revolutionary present” (Bidoun).